The Regulatory Journey from a European Perspective

A Discussion Paper authored by

Dr. Georg Serentschy

Revised and updated version

August 02, 2021

This article is also available as a pdf-version under the tab „Download“

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Executive Summary

3. Drivers behind the relationship between innovation and regulation

4. From current regulatory challenges to ‘Anticipatory Regulation’

4.1. Challenges and pressures on national regulators.

4.2. Anticipatory Regulation.

4.3. Regulatory Sandboxes.

4.4. High time for regulatory innovation – a new role for BEREC?

5. From Regulation 1.0 to Regulation 4.0 – A Personal Recap.

5.1. Regulation 1.0 – opened telecom markets.

5.2. Regulation 2.0 – a new perspective on innovation, investment, and regulation.

5.3. Regulation 3.0 – birth of the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC)

5.4. Regulation 4.0 – Regulation for all Digital Players.

6. Technology – Innovation – Regulation.

6.1. The innovation – regulation paradox.

6.2. A call for an innovation-open regulation and policy implications.

6.3. The disruptive evolution of the ICT ecosystem over the last 20+ years.

6.4. Threats and Opportunities for Traditional Mobile Network Operators (MNOs)

6.4.1. Disruption of the traditional B2C/B2B businesses.

6.4.2. Cloudification, Network Slicing and New Operator Paradigms.

6.4.3. Asset Monetization and Reconfiguring Telco Assets

6.4.4. The MNO – Vendor Relationship Reloaded.

6.4.5. New Opportunities for Telcos.

6.4.6. 5G Changes User Behavior

7. Outlook and potential future research areas.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations.

9. Closing Remarks and Acknowledgements.

10. Annex – The EU Digital Agenda.

10.1. The Big Picture.

10.2. The European Commission’s new digital policy initiatives.

10.3. DSA and DMA.

10.4. The „Digital Compass 2030: The European Road to the Digital Decade“.

1. Introduction

Reasons for a revised version of the article: Following the first publication of this policy paper on 23 May 2021, I have gratefully received numerous valuable responses from regulators and regulatory experts, industry representatives and consultants. This updated version considers many of the suggestions received, especially about the operationalization of my suggestions for practitioners, some important clarifications, and better definitions, but also about a better theoretical foundation of my theses. Finally, a few linguistic clarifications have also been made where necessary.

New aspects considered: Through additional literature study, I have encountered new aspects that have significantly expanded my work, moving it more in the direction of a balanced 360-degree overview of the subject. In this new version of my article, I not only address the upheavals in the ICT ecosystem from 2000 to 2020, but also the massively changed environment for regulators and the challenges and pressure they are facing. These changes are reflected in particular in the newly written section 4 and extended or supplemented other sections.

The complexity of the topic requires thematic delimitation and therefore I make a few definitions and clarifications right at the beginning: Mainly for resource reasons, this article focuses on technical aspects of innovation and only touches on the social aspects of innovations and innovation processes in passing. For me, it is undisputed that every innovation has social implications and that, on the other hand, there are also social trigger points for technical innovations. The Corona pandemic has shown us just how much technical innovations, which before the pandemic had predominantly led a niche existence, such as videoconferencing, became a global mass phenomenon overnight, as it were.

In the same vein, I will not go into the regulatory and ethical challenges associated with artificial intelligence and its applications here, as this is beyond the scope of this paper and the resources required. Similarly, I do not address issues of innovation and regulation in other industries, such as financial markets, medicine and pharmaceutical development, or transportation, but focus here on the digital industry and the telecom sector in particular.

Regulation is and was always contested and discussion about regulation hovers between ‘more’ or ‘less’ of it, and whether activity x or y should be regulated. As a former regulator working as an advisor in and outside Europe, it strikes me that when it comes to the issue of regulating the digital industry and the telecommunications industry, there is often a remarkable black-and-white view, with two diametrically opposed camps. On the one hand, there are the advocates of blanket deregulation who want to leave everything to the market, and on the other hand, there is the regulatory orthodoxy, the almost religious-looking representatives of the group who want to immediately press every innovation into a regulatory straight-jacket without even waiting to see how an innovation develops. This is ostensibly done with justifications such as protecting the innovation process or protecting consumers from the supposedly harmful consequences of this very innovation. Yes, and then there is also a public lament that there is no „Silicon Valley“ in Europe and that start-ups very often emigrate there precisely because they expect better conditions there. How does all this fit together and is there perhaps a mediating forward looking position? In other words, aren’t we in Europe shooting ourselves in the foot again and again with often excessive or wrongly placed regulations and at the same time complaining that innovations and new jobs are largely at home in other parts of the world?

We need a new approach to innovation: My motivation for writing this discussion paper comes from the perception that we need in Europe a new, more relaxed, and welcoming approach to innovation and more courage to experiment. With this contribution, I do not claim to present an academic article, but rather a paper that is intended to stimulate reflection for those involved in the policy making and the innovation process. It should be remembered that regulators, public R&D agencies, and policymakers play an eminently important role in this process, and that science, industry and politics need to open a new chapter in their interactions with each other so that regulation stimulates innovation and does not stifle it.

Over- and under-regulation failed government policies and red tape are toxic for innovation: In this context, it should not be forgotten that not only external factors such as overregulation or misplaced regulation can stifle innovation, but also internal factors such as bureaucratic company rules and cumbersome and lengthy internal company approval processes can act as innovation stoppers. Similarly, over-bureaucratized processes in public administration, fragmented or flawed policies, or the lack of funding opportunities can lead to innovations being developed with the help of public funds, but the company „emigrating“ to another place once the innovation reaches a certain level of maturity because it finds more advantageous conditions there for the commercial deployment of the innovation. Such incidents represent a wake-up call to policymakers to develop a better interlinked and long-term combined R&D and industrial policies.

On Twitter, I found a perfectly fitting quote from Cedric O, the French Secretary of State for Digital Transformation and Electronic Communications, which underscores the above theme: “The USA has the FAANG, China has the BATX, Europe can’t only have the GDPR. It’s time to have our own technological sovereignty and stop depending on US or Chinese solutions!” This statement perfectly addresses why Europe needs a policy aimed at strategic autonomy and digital sovereignty (see also section 10.1). In an ITS webinar on Open Strategic Autonomy (OSA) on January 27, 2021, one of the key takeaways was that being a „regulatory superpower“ is a helpful – or even necessary – but not sufficient condition for global success. Setting standards in many areas, even beyond Europe, such as the GDPR and the Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive is good, but that alone will not be sufficient to secure Europe a place in the global top league and accelerate the post-pandemic recovery. By implementing OSA, I see an opportunity for Europe to gain the means to increase its sovereignty and become a global superpower.

Technology progress challenges industry and regulators equally: In this discussion paper, I would like to provide an overview of the development of regulation in the telecommunications and digital sector, how this is driven by technological progress, what challenges and opportunities traditional telecommunications companies face today, and what innovation-friendly regulation might look like. However, in this revised version of my article, I also address the other side of the coin, namely what challenges and external influences regulators face today and what role regulatory innovation could play for them individually and institutionally. Lastly, I also suggest how regulatory innovation could be introduced into daily practice.

An important caveat: This paper reflects my current thinking on the relationship between innovation and regulation, and what policies are best suited to foster innovation from a regulatory perspective. It is a work in progress, and I may revise and add to my views after further discussion results, review, and analysis of new data and materials.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The newly written section 4 addresses regulatory challenges for regulators and how regulatory innovation could be introduced in the daily practice. Section 5 describes, from a backward-looking perspective, how regulatory goals and their respective paradigms have evolved over the last 30 years and what their main actors are. Section 6 describes the innovation-regulation paradox and presents a proposal for a more agile approach, followed by a list of threats and opportunities for traditional telecom operators. Section 7 provides an outlook and lists some areas for future research. Section 8 concludes. In the annex (section 10), I provide a quick overview of the European Commission’s new digital initiatives, as well as the policies and strategies behind them, how they interrelate, and what they may mean for the industry. It should be emphasized that I limit myself here to a high-level overview, with the aim of providing perspective, context, and food for thought.

At this point, I would like to express my sincere thanks to all readers of my discussion paper who were involved in the creation of this updated version. Without the valuable feedback from regulators and subject matter experts, this revision would not have been possible. I am convinced that the revised version now available has gained both in quality and balance.

2. Executive Summary

The tension between regulation and innovation has been going on for decades. Innovation is always new and uncertain and therefore risky, while regulation implies – inter alia – control, as in controlling the risk of new, unproven ideas or products. However, global competition and the pace of innovation has put us – especially in Europe – in the situation where trying to control innovation from the outset or even preventing it from happening in the first place has become, on balance, riskier for society and business than sandboxing it and then deciding whether regulation may be needed.

In NESTA’s seminal paper “Renewing regulation – ‘Anticipatory regulation’ in an age of disruption” (March 2019), the tension between regulation and innovation was well described: Unhelpfully, public and political discussion about regulation has typically pivoted between theoretical (or theological) arguments about whether we should have ‘more’ or ‘less’ of it, and whether activity x or y should be regulated. Far less attention has been paid to the actual practice of regulators, in particular as it relates to innovation. With this policy paper, I would like to contribute to the discussion on what regulators can do in their regulatory practices to foster innovation rather than stifle it.

To resolve the paradox between regulation and innovation, I advocate a different approach to regulation – agile policy making – that allows each new idea or innovation the time to develop its opportunities and possibilities, at least in early form, before the call for regulation is made. The „right time“ for eventual regulation depends on the question when an innovation becomes socially, politically, technically, or economically relevant. This leads to the question, how can we set up a system which is able to better synchronize technological constructions (innovations) and social constructions (legislations and regulations).[1] The “right time” for potential regulatory interventions depends on the available technological choices. As soon as the technological construction (innovation) is casted in stone as it were (i.e., no choices are available), it is too late for an agile policy making. This shows that timing is very critical and calls for more research on how to better manage the innovation-regulation system.

From a personal retrospective, I present the regulatory journey of the last 30 years in fast motion, so to speak, from Regulation 1.0 to Regulation 4.0 with its essential constituents in each case.

This part is followed by an overview of the disruptive developments from the ICT ecosystem 2000 to the ICT ecosystem 2020, topics such as cloudification, new operator paradigms, asset monetization, new developments in operator-vendor relationships, and ultimately some new opportunities for telcos. As can be seen, all this turns the strategic and regulatory agenda of telcos upside down, but also requires a new approach from regulators and other relevant authorities. Key conclusions are drawn and some illustrative areas for future research are identified.

3. Drivers behind the relationship between innovation and regulation

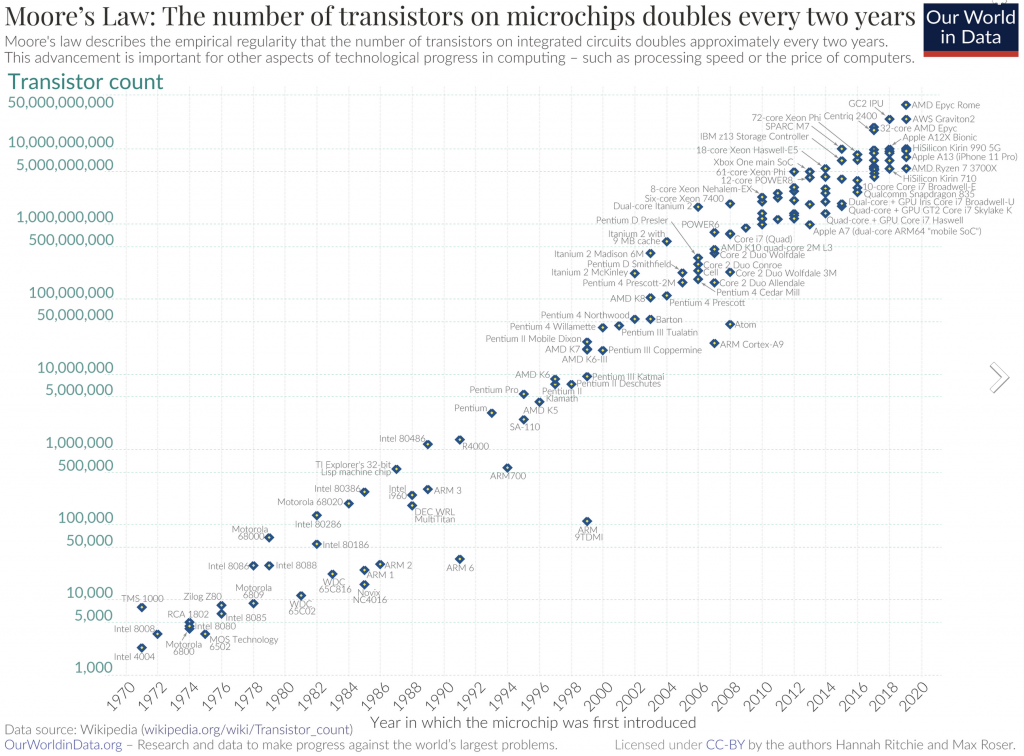

Developments in the field of electronic communications services and networks are driven by a seemingly never-ending stream of technological advances and the resulting product and service innovations. A key driver of this development is the progressive evolution of electronics and software with Moore’s Law as the underlying paradigm. This essentially states that the performance of electronic circuits doubles every 12 – 24 months (Exhibit 1).

There is a very telling anecdote[2] – notably from a US perspective- about the impact of Moore’s Law and how important it is to recognize it timely: Qualcomm and CDMA versus TDMA.[3] In the early days of mobile telephony, the European Commission mandated the standard (GSM/TDMA), and US government allowed the market to choose. By 1991 Qualcomm had persuaded a dozen or so American telecom companies to undertake large-scale tests of CDMA technology. Once again, a serious discussion about standards started in America and in 1993, the industry body CTIA accepted CDMA as an American mobile phone standard. In the words of Irwin Jacobs, the visionary person behind the CDMA standard and co-founder of Qualcomm: “One key reason we won was that even though CDMA was more complicated to implement, people was just thinking about the capacity of chips at that moment in time. They were not taking into account Moore’s law that would allow the technology to improve every two years and enable the greater efficiency that could be achieved through CDMA.” People say that in hockey you don’t go where the puck is, you go to where the puck is going. And Qualcomm went where the puck was going – to Moore’s law. Since then, for good reasons, a strict principle of technology neutrality prevails in Europe.

Exhibit 1 – Moore’s Law in a semi-logarithmic presentation (source: OurWorldinData.org)

At the first glance, it seems to be natural, that the design of the legal and regulatory framework and the development of the corresponding policy fields always lags behind technological developments. In my view, it is always somewhat sobering to be faced with a problem that seems “natural” and therefore not changeable. But is that really always the case? Are there no examples of closer and constructive interaction between regulation and innovation? I think there are such examples, we should look for them and analyze them and try to learn from them:

-

Kevin Werbach provides an interesting example for a constructive relation between innovation and regulation: “How to Regulate Innovation — Without Killing It”. “Both Skype and Uber were companies that when they started were illegal in most jurisdictions. Skype was illegal in most of the world when it launched, because there were rules saying you could not do a communications service, a telephone service, outside of the existing regulatory infrastructure. In the U.S., because of what we did [at the FCC in the 1990-ies], we very deliberately left open the door. Even though things like Skype were outside of the regulatory structure, we made a conscious decision to allow them to develop. And that’s an example of regulators consciously deciding not to impose a whole set of rules early on — when these were nascent technologies — allowing them to grow”. And Uber was a similar story. This shows that government can actually be a positive force in innovative markets.

-

An interesting regulatory example from the energy sector aimed to promote innovation can be found in a recent interview with Jochen Homann, President of the German Federal Network Agency BNetzA. „Regulation is not an instrument of economic promotion, but serves consumer protection and the prevention of monopolies,“ says Jochen Homann, who intends to protect the „innovation hydrogen“ by excluding advantages for established gas network operators who want to have the conversion of their networks financed by the „natural gas customers who are dying off“, in order to create a level playing field for new players on the hydrogen market. As is well known, there is a fierce dispute in the gas industry about the form of future hydrogen regulation; the gas network operators in particular (in the telecommunications market they would be called „incumbents“) are campaigning for common regulation. Homann, on the other hand, does not think it makes sense to „impose“ regulations from the natural gas network sector, partly because of different market roles and network typologies. „Gas network regulation has grown over decades and regulates problems that do not even exist in the hydrogen sector,“ Homann argued.

-

There is reportedly evidence of the positive impact of principle-based regulations in the area of car safety, that because of them semiconductor manufacturers have brought to market many innovations in microelectronics that otherwise would not have come or would have come later.

-

According to a McKinsey study 2019, there is another example from the car industry on the regulatory change in product cybersecurity. Regulators are preparing minimum standards for vehicle software and cybersecurity that will affect the entire value chain. Cybersecurity concerns now reach into every modern car in the form of demands made by regulators and type-approval authorities. For example, in April 2018, California’s final regulations on autonomous vehicle testing and deployment came into effect, requiring autonomous vehicles to meet appropriate industry standards for cybersecurity.

-

In general, regulations in the area of personal safety, be it in aviation, manned spaceflight, road and rail traffic, etc., seem to have led to innovations being implemented very quickly and purposefully, perhaps also because these rules were written „in blood“, as it were.

This suggests that with the right balance and interplay between regulation and innovation, companies are motivated to innovate, they “swing for the fence”. To put it in more abstract terms, the question is, how can we set up a system which is able to better synchronize technological constructions (innovations) and social constructions (legislations and regulations). It is thought-provoking that the positive examples of innovation-enhancing regulation that I have been able to find are not in the telecommunications industry. I’m not saying that they don’t exist, but despite some effort I couldn’t find them. In any case, it would be worth paying more attention to this aspect in regulatory practice for the telecom industry. In my view, sandboxing is probably the answer to allow agile policy and law making.

To sum up, the tension between regulation and innovation has been going on for decades. Innovation is always new and uncertain and therefore risky, while regulation implies – inter alia – control over the unknown, such as limiting the risk that comes from new, unproven ideas or products. However, global competition and the pace of innovation (Moore’s Law!) has put us – especially in Europe – in the situation were trying to control innovation from the outset or even preventing it from happening in the first place has become, on balance, riskier for society and business than sandboxing it and then deciding whether regulation may be needed (see section 4.3.).

4. From current regulatory challenges to ‘Anticipatory Regulation’

4.1. Challenges and pressures on national regulators

This section is strongly inspired by a landmark study, conducted by NESTA[4] in March 2019, “Renewing regulation – ‘Anticipatory regulation’ in an age of disruption”.

Regulators have always been caught in the crossfire between policy makers, consumers, as well as the industry they are charged with regulating. In addition, there are the lobbying groups that support the respective stakeholders and, more recently, various NGOs that make their voices heard with the help of social media and political support.

What is new, however, is the growing pressure that regulators are under, triggered by massive technological change and increasing complexity of the stakeholder environment. Disruptive technologies and persistent internal resource constraints that prevent tracking or sometimes even fully understanding these changes are becoming a commonplace experience among many regulators, in particular for regulators in smaller countries with rather limited resources. This is compounded by outdated or even dysfunctional structures of some regulators that prevent them from effectively dealing with the new challenges. Institutional rivalries that inevitably arise from such structural shortcomings tie up resources unnecessarily and do not help to improve the situation.

This leads to growing uncertainty among many regulators about when and where to encourage (or even stimulate) innovation, or which innovations they believe they need to curb or even prevent to control their impact on consumers and society. Regulators are caught in the crossfire of these debates and the combination of uncertainty about the accelerating pace of technological development and the growing pressure from various stakeholder groups understandably very often leads to falling back on or sticking to „successful recipes“ from the past.

I think that this dilemma, which many regulators face, admitted or not, could or better should be solved on BEREC level, however, that would also require a new understanding of what BEREC is supposed to and is allowed to do.

External pressure on regulators has been built up from various sides (see the NESTA study mentioned above, from p. 15 onwards). Moreover, there is also a great deal of uncertainty among many regulators about the future and about the emerging shift away from traditional regulation.

-

Institutional change: Will traditional NRAs that have expertise in ex-ante regulation, design of remedies, market monitoring etc. also be used for similar tasks in new subject areas? For example, as an advisory and monitoring body for platforms. This could simplify the replacement of existing tasks and support institutional change. A recent proposal by the European Parliament’s Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection’s Rapporteur broadly goes in the same direction, addressing the set-up of a “European High-Level Group of Digital Regulators in the form of an Expert Group, consisting of the representatives of competent authorities of all the Member States, the Commission, relevant EU bodies and other representatives of competent authorities in specific sectors including data protection and electronic communications”.[5]

-

Erosion of sectoral boundaries. General-purpose technologies such as new methods of data capture and processing, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies have wide-ranging impact across traditional sectoral boundaries. Few individual regulators have the technical capabilities, market insight or leverage to cope with the broad range of issues that such general-purpose technologies create in their domains. There is a growing capability and power asymmetry between regulators and, in particular, global technology firms, with the latter having a virtual monopoly on the best technical talent and immense financial firepower with which to protect their commercial interests.

-

Accelerated scaling and radical uncertainty. Many technologies today can scale with unprecedented speed, creating a great deal of short- and long-term uncertainty around their wider consequences. Permissionless innovations (which require little or no regulatory approval) can become ‘facts on the ground’, with millions (or billions) of users, before regulators have engaged with their potential implications. Facebook has in 15 years reached 2.3 billion monthly active users, and virtual market saturation in many economies. This rapid growth can enable new types of public harm, for example: the ability of illegal content to disseminate with unprecedented scale and rapidity through online channels. Where this rapid scaling is global, regulatory action at the national level can be impractical, and yet infrastructures to respond effectively and quickly do not typically exist at the supranational level.

-

Innovation and regulator/policymaker jurisdictional tensions. As is the case with ‘fairness’, regulators often lack – or feel they lack – the legitimacy to make decisions about values that are less subject to quantification. This is particularly problematic in the context of innovation and uncertainty, where quantitative approaches to decision-making may be unavailable or misleading. While a range of techniques now exist to assess the public’s priorities in these cases, it is not always clear how these should be applied. Usually government must set strategic direction, but too frequent (“micro-managed”) or granular intervention can undermine regulatory independence, create regulatory uncertainty, and discourage private investment.

-

Unaccountable platform governance. Commercial digital platforms play an increasingly important role in our lives, and some of these are the greatest commercial success stories of our times. Where technology lowers barriers to entry, platforms often emerge to facilitate trade. Platform operators set rules to maximize the platforms’ value; since this is generally related to the value it delivers to its users, incentives are broadly aligned.

-

Growing role of firms in fulfilling previously public functions. As the transformative power of technology drives some public agencies to the limits of capacity and jurisdiction, private companies have acquired growing responsibility for some previously state-led functions. Social media and video sharing services increasingly play a vital role in enforcing anti-terrorism law online, and potential changes to EU copyright legislation could extend their responsibilities. Regulators may not be equipped with the remits, expertise, or data to respond to problems like these, which are more to do with law enforcement than regulation in its traditional sense.

4.2. Anticipatory Regulation

The phrase “Anticipatory Regulation” was coined by NESTA in 2017. NESTA developed new ways of thinking about regulation and working to show what it means in practice. NESTA considers the impact this approach could have on the UK’s global competitiveness and explore how it could be used to capture the benefits of emerging technologies and harness them for public good. In 2012, NESTA analyzed the relationship between regulation and innovation in The Impact of Regulation on Innovation. In a more recent paper “Renewing regulation – ‘Anticipatory regulation’ in an age of disruption” (March 2019), NESTA elaborated in more detail on “Anticipatory Regulation.[6] Traditional ways of regulating are struggling to cope with the pace of change in technology.

Anticipatory regulation is a new approach that is proactive, iterative, and responsive to evolving markets. Thus, this new approach is better suited to keep pace with an environment driven by Moore’s Law. The anticipatory approach emphasizes flexibility, collaboration, and innovation. It is built on six principles which in many ways contrast with traditional regulatory practice (see exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Six principles of anticipatory regulation (Source: NESTA)

4.3. Regulatory Sandboxes

Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) and financial regulators pioneered with introducing “Sandboxes” as a supervised “safe space” for piloting and testing innovatory products, services, business models or delivery mechanisms of participating organizations in the real market, using the personal data of real individuals. The Sandbox provides an opportunity for accountable organizations and innovative regulators to work and learn together in a collaborative fashion to enable all the benefits of the digital transformation of our society and economies and the protection of individuals privacy and personal data.

Regulatory Sandboxes are gaining traction with European Data Protection Authorities.[7] Since the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (the “ICO”) completed its pilot program of regulatory sandboxes in September 2020, two European Data Protection Authorities (“DPAs”) have created their own sandbox initiatives following the ICO’s framework.

-

The Datatilsynet Sandbox Initiative for Responsible Artificial Intelligence: The Norwegian DPA (the “Datatilsynet”) launched its sandbox initiative in 2020. The goal of the initiative is to promote the development of innovative AI solutions that are ethical and responsible. It also will help organizations implement privacy-by-design solutions and enable compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”). The Datatilsynet intends to leverage the learnings and insights arising from the sandbox projects to further develop its own competence in this area and to develop guidelines relevant to organizations implementing AI. The Datatilsynet received 25 applications from diverse public and private organizations before the January 15, 2021, deadline. The Datatilsynet reviewed applications to select four projects (considering varying types and sizes, across different sectors) that entered the sandbox by mid-March 2021.

-

The CNIL Sandbox Initiative for Health Data and Privacy-by-Design: On February 15, 2021, the French DPA (the “CNIL”) launched its own sandbox initiative (in French) that covers innovative projects in the healthcare sector that make use of personal data. The objective is to help organizations implement privacy-by-design from the outset. The call for application (in French) was open until April 2, 2021.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) Regulatory Sandbox has inspired similar initiatives among regulators across the world. The regulatory sandbox allows businesses to test innovative propositions in the market, with real consumers. The sandbox is open to authorized firms, unauthorized firms that require authorization and technology businesses that are looking to deliver innovation in the UK financial services market.

The FCA sandbox seeks to provide firms with:

- the ability to test products and services in a controlled environment

- reduced time-to-market at potentially lower cost

- support in identifying appropriate consumer protection safeguards to build into new products and services

- better access to finance.

The FCA closely oversees the development and implementation of tests, for example by working with firms to agree bespoke consumer safeguards. Sandbox tests are expected to have a clear objective (e.g., reducing costs to consumers[8]) and to be conducted on a small scale. Firms will test their innovation for limited duration with a limited number of customers.

Regulatory sandbox tools: The regulatory sandbox provides access to regulatory expertise and a set of tools to facilitate testing. The tools are not always needed, and their value will depend on the nature of each business and their test.

Restricted authorization: To conduct a regulated activity in the UK, a firm must be authorized or registered by us, unless certain exemptions apply. Successful firms will need to apply for the relevant authorization or registration in order to test.

The FCA have a tailored authorization process for firms accepted into the sandbox. Any authorization or registration will be restricted to allow firms to test only their ideas as agreed with us. This should make it easier for firms to meet FCA’s requirements and reduce the cost and time to get the test up and running.

4.4. High time for regulatory innovation – a new role for BEREC?

It is striking that, to the best of my knowledge, regulatory innovations such as anticipatory regulation or sandboxing have not yet been developed or applied in the telecommunications environment. If this finding is correct, we are obviously dealing with a particularly structurally conservative environment in the telecoms regulatory field, and it would therefore be high time to open the doors to allow regulatory innovations. And not to forget, courage to let go and „leave behind“ needs new responsibilities!

I suggest setting up a BEREC working group to look at regulatory innovation, applicable best practices from other sectors, and implementing sandboxes in the regulatory practice. This includes in particular the question in which areas sandboxing can be helpful. Certainly, in the area of spectrum awarding, new licensing models, support for private arrangements (spectrum sharing, network sharing, infrastructure sharing, local and central access, etc.) instead of regulations. Members of this working group could support NRAs to experiment with these innovations.

5. From Regulation 1.0 to Regulation 4.0 – A Personal Recap

5.1. Regulation 1.0 – opened telecom markets

Traditional competition law, which by its very nature is based on an ex-post analysis of markets and market participants, was therefore supplemented about 30 years ago by an ex-ante regime that imposes ex-ante obligations based on ex-post status analyses (e.g., determination of market power). This is the basis of the model of traditional telecom regulation („Regulation 1.0„), which became the standard with the onset of market liberalization. The initially successful Regulation 1.0 (1990 – 2003[9]) transformed in nearly all European countries inefficient monopolies into a vibrant competitive landscape. This landscape was characterized by telecom companies competing and the outcome was understandably hailed as a success.

However, already towards the end of this phase, voices were raised to move back to more ex-post and less ex-ante regulation. According to people, familiar with the matter, this was also reflected in ‘very engaged’ internal debates on European Commission level between the ex-post camp (DG COMP) and the ex-ante camp (DG CONNECT). At that time, there were even considerations to reduce or abandon ex ante regulation, which, as is well known, was only ever planned as a market opening instrument for a limited period. It is also not surprising that institutional rivalries between the ex-post camp and the ex-ante camp manifested themselves not only at the European level, but also at the national level. Interestingly, since then, the regulatory regime from 1.0 to 4.0 always hovered between the poles of more ex-ante and less ex-post to more ex-post and less ex-ante regulation. Regulation 4.0 proposes again a more ex-ante approach, but we will come to this later.

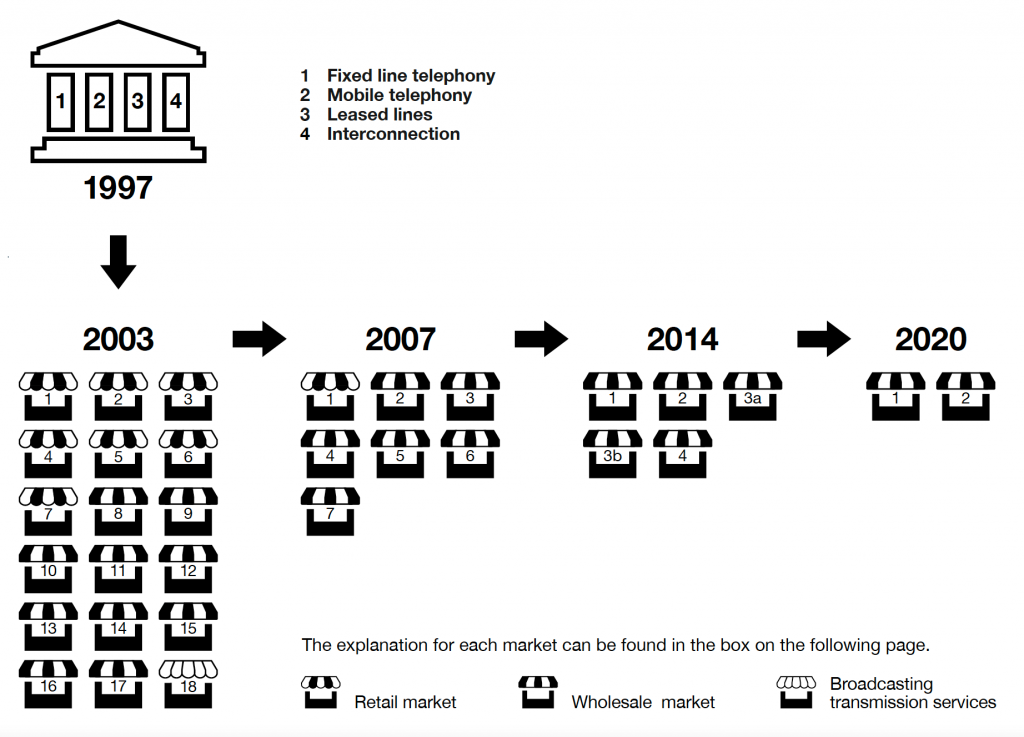

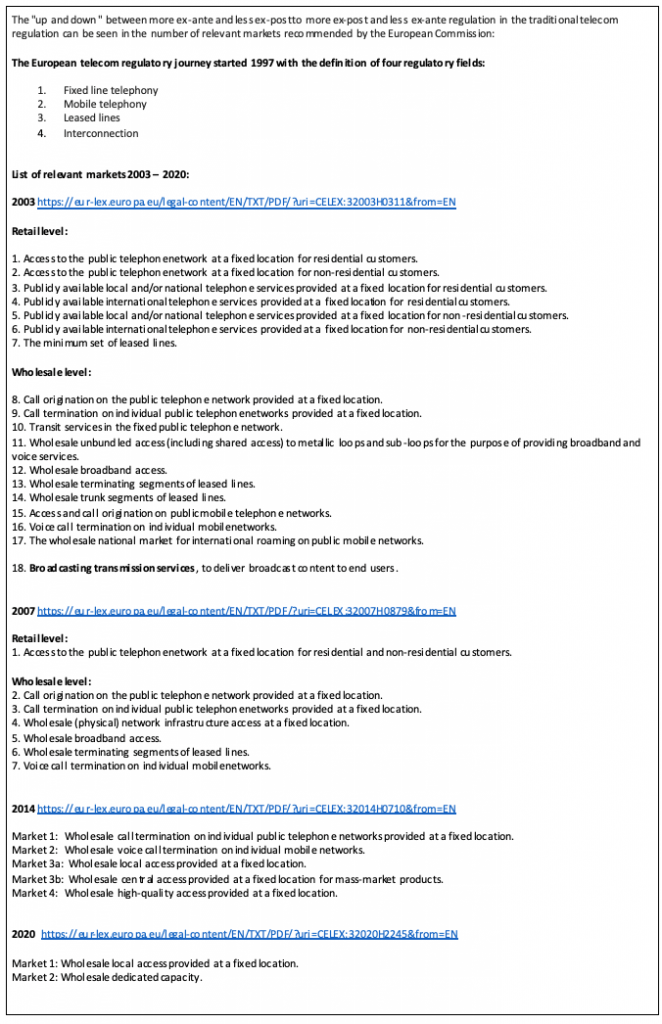

Exhibit 3: Number of relevant markets over time (Source: own research)

This „up and down“ between more ex-ante and less ex-post to more ex-post and less ex-ante regulation in the traditional telecom regulation can also be seen in the number of relevant markets recommended by the European Commission, which reached an all-time high of 18 relevant markets (including one broadcasting market) in 2003 from originally (1997) four regulatory fields (fixed, mobile, leased lines and interconnection), only to drop to 7 markets (including one retail market and 6 wholesale markets) in 2007. This trend continued with the 2014 market recommendation, which included only 5 wholesale markets and no retail market. Most recently, in December 2020, the market recommendation only provides for two wholesale markets. Exhibit 3 illustrates this development.

It is interesting to observe that the regulatory cycles from 1.0 to 4.0 have become shorter and shorter over time, and most recently also overlap timewise: Regulation 3.0 (the EECC) has not even been implemented nationally in all EU countries today and at the same time the EC is already publishing its proposals for Regulation 4.0 (DSA and DMA). At the same time, there are also stronger ex-ante elements not only in sector-specific regulation, but also in platform regulation. General competition law also incorporates ex-ante elements, e.g., with the 10th GWB amendment in Germany in Article 19a.

5.2. Regulation 2.0 – a new perspective on innovation, investment, and regulation

Influenced by my understanding of the market and more than a decade of hands-on regulatory experience, I presented reflections on a paradigm shift in regulation in 2013 at the end of my tenure as a regulator with my book Regulation 2.0, in which I systematically pointed out the interrelation between innovation, investment and regulation for the first time and argued for limiting traditional regulation.

I intend to provide a summary of my book at this point, but I must admit that eight years after its publication – influenced by many years as an industry consultant – I see several things more critically than I did back then. My view at that time was probably quite revolutionary for a regulator, but eight years in this business is also a long time and the telecom sector has changed massively since then. I therefore ask the reader to take this caveat into account.

With this book, my co-authors and I wanted to highlight the importance of ICT and the responsibility of sector-specific regulators. Therefore, one key issue is how regulatory policies can be shaped to react to the challenges. We as a regulatory authority deal with these issues daily. However, regulators are very much restricted by long-term policies designed on EU-wide and national scales. Consequently, approaches we would find optimal for fostering the ICT industry are often hampered by slow administrative and legal processes.

We have shown in this book that Europe is falling behind in key areas of the telecommunications sector and that policy and, often, cultural changes in these are needed to overcome the growing gap compared with other parts of the world.

When my co-authors and I designed the propositions described in “Regulation 2.0” – the core of this book – we considered information and proposals from many stakeholders, including consumers, regulated and non-regulated market players and other industry experts. We decided that it would be very valuable to have such input included in this book. Bernstein Research analyst and telecommunications expert Robin Bienenstock agreed to contribute a section (Chapter 2) about how the financial world views current challenges and the future of the European telecommunications sector. Providing only the headline to her, we left it to Robin Bienenstock to describe her views of sector-specific regulation. Since a regulatory authority naturally has a different point of view than financial representatives (for instance, focusing more on consumers), we expected a good comparison between the two perspectives.

Robin Bienenstock concluded that three initiatives would help foster investment in telecommunications infrastructure:

- De-regulation of fiber.[1]

- Creation of a long-term spectrum plan with clear rules and dates, including the harmonization of radiation limits.

- Tightening of the regulatory process such that either fewer participants are involved or that decisions are binding enough to remove ambiguity of outcome.

We also offered our approach to solving the identified problems, starting with a new set of regulatory policies (“Regulation 2.0”), calling for a more dynamic approach to regulation, with an emphasis on policies that foster intermodal competition. We also proposed organizational reform with a strengthened BEREC Chair as a focal point. We have explicitly expressed the view that a change in regulatory policy in this direction will create the optimal framework for efficient investment in new infrastructure.

Another of our insights is that regulatory policies alone are not sufficient to foster the ICT sector. Regulation and other policy areas, such as innovation and investment, are interdependent. This interdependence creates a “virtuous circle”, where innovative services are likely to increase demand for (high-speed) broadband; increased demand leads to more investment, as the willingness to pay rises, which, in turn, creates incentives for providing new bandwidth-intense services. Regulatory and investment policies should provide the right frame such that investment in new infrastructure naturally follows.

Hence, we proposed concrete policy suggestions for innovation and investment. To foster new services, innovation in education, the facilitation of new business models and support for the start-up scene is critical. Our propositions in each of these areas, we pointed out, will go far in creating the best environment for new, innovative services.

In the area of investment policies, we call for pension funds and other infrastructure investors to engage more in infrastructure competition and elaborate possibilities, how cooperation models and public financing can help. Finally, we have reflected on the activities and achievements of the Austrian chairmanship of BEREC in 2012.

The book Regulation 2.0 is structured as follows:

1 . In Chapter 1, we examined how regulation in European telecommunications markets has evolved over the last 20 years. Particularly, we focused on the role of the “Ladder of Investment”[2] and outlined the main changes that the industry has faced during this time. We also described upcoming transformations in the telecommunications sector.

2. In Chapter 2, as noted, Robin Bienenstock provided her view on how regulatory policies may address some of the problems the European telecommunications industry is facing. She also approaches some delicate issues such as the possibility of a “European regulator.”

3. In Chapter 3, we shared our view on what can be done to bring Europe back to the top in the information and communications industry. While we provide input to the discussion on how regulatory policies might take shape in the future, we also touch on issues that are usually not the main focus of regulators, such as innovation and investment policies. However, these are essential, as new services and sufficient financial capital are important for the telecommunications sector to develop. Moreover, innovation will influence how regulatory policies need to be designed in the future. We argue that Regulation, Innovation, and Investment work together as a “virtuous circle” that can boost the European ICT sector.

Finally, in Chapter 4, we looked back on my 2012 BEREC Chairmanship and discuss its targets and achievements based on the BEREC Work Program 2012.

5.3. Regulation 3.0 – birth of the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC)

If one wants to stick to this – non-scientific – nomenclature, one could call the introduction of the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) end of 2018 „Regulation 3.0„. For the first time, this competition landscape was not only characterized by telecom companies competing, but also telecom companies competing fiercely with digital platforms (OTT-players).

It was the European Commission’s explicit objective to create stronger incentives for investing in new, fiber-based infrastructure, in a bid to resolve the investment bottleneck that had built up around Europe’s digital infrastructure.[10] At the same time, however, the regulatory focus was to remain on encouraging competition, and any conflict of objectives between investment incentives and competition was to be avoided.

A new explicit objective has been introduced, to substantially improve connectivity within the EU, to allow broad participation of its citizens and to move forward digitalization of the economy. The primary aim here was to increase public welfare by utilizing the socio-economic effects generated through digitalization.

Further key elements of the EECC are:

- An overhaul of the European spectrum policy,

- The introduction of a co-investment model, and

- Better rules for state aid.

My assessment of the EECC from an earlier perspective can be found here.

5.4. Regulation 4.0 – Regulation for all Digital Players

From a high-level perspective, it seems that Regulation 4.0 is fundamentally different than the previous paradigms. Regulation 1.0 to 3.0 are, in some sense, about regulating markets (whether from a static or dynamic perspective) whereas Regulation 4.0 is about regulating networks or platforms, which have a different set of properties than markets.

The European Commission (EC) has announced several new legislative initiatives, and a small number of them have already been implemented. Here, too, the EC’s initiatives were driven by the desire to place disruptive developments (OTTs, digital platforms, social media, etc.) in a new overall regulatory framework („Regulation 4.0„). Among other things, the same pattern of a combination of ex-post and ex-ante elements can be found here again. The fundamental tension between the extent to which these regulations actually protect users in the long term and contribute to diversity of supply, or whether they are more likely to slow down innovation and investment and thus contribute to Europe falling further behind Asia and the US, will continue to occupy us intensively in the coming years.

The new data economy, multi-sided markets, the rise of platform-based business models and the growing importance of cross-market digital ecosystems are the game changers in the digital economy. One of the characteristics of the digital economy is the interplay of these different aspects within a process which can lead to the emergence of new positions of power, their perpetual reinforcement, and the ability to leverage them to other markets.

In this context, it is interesting to see, that the German government set up in September 2018 a ‘Competition Law 4.0 Commission’ under the auspices of the Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). This Commission was tasked with drawing up recommendations for action for the further development of EU competition law in the light of the digital economy.

The Commission ‘Competition 4.0’ recommended in September 2019 inter alia:

-

that competition authorities make greater use of flexible, targeted remedies in digital markets. It recommends that the European Commission conduct a study which analyses the previous policy on remedies pursued by the competition authorities in relevant cases (Microsoft, Google Shopping, etc.).

-

that a dominant online platform falling under the Platform Regulation shall be prohibited from favoring their own services in relation to third-party providers unless such preferencing is objectively justified.

-

the formulation of cross-market principles guided by competition law in a framework directive based on Art. 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) stating when and how users should be granted a right to make a digital user account accessible to third-party providers. The European Commission should be authorized to enact sector-specific regulations to flesh out these rules.

A summary of these recommendations in English language can be found here, the full report of the Commission in German language can be found here. For more details about Regulation 4.0, see Annex.

6. Technology – Innovation – Regulation

Let’s start with the future of the telecommunication business and the interactions with regulation. Sections 6.1 and 6.2 are addressing the relation between innovation and regulation, section 6.3 describes at high level the disruptive evolution of the ICT ecosystem over the last 20+ years and derives conclusions from it. Before going into this, let me start with an important disclaimer: I am not trying to predict the future, I only intend to outline possible scenarios as food for thought.

6.1. The innovation – regulation paradox

Figuratively speaking, regulation does not fall from the sky. In an industry driven by technological innovations with Moore’s Law as the pacesetter, law making, and regulation often lags behind technological advances. It is even more difficult for ex-ante regulation because the success of new technologies and innovations cannot be assessed ex-ante. Fatally, this means that the regulatory focus is often on the wrong issues. Unfortunately, this means that regulatory solutions are often imposed on the market for which there is not yet a problem or no longer a problem. My working assumption is, that industry, policymakers, consultants, and regulators are all equally smart on average, yet it is fundamentally impossible for all these groups to predict innovations or business cases. When it is tried anyway (as it happens from time to time), it was and is doomed to fail. This is an intrinsic paradox and the root cause of the innovation-regulation problem. It then follows that without changing the innovation – regulation interplay this paradox cannot be solved.

6.2. A call for an innovation-open regulation and policy implications

Agile Policy making. I advocate a different approach to regulation that allows each new idea or innovation the time to develop its opportunities and possibilities, at least in early form, before the call for regulation is made. The „right time“ for eventual regulation depends on the question when an innovation becomes socially, politically, technically, or economically relevant. The issue of relevance could be defined, for example, by a set of criteria. This leads to the question, how can we set up a system which is able to better synchronize technological constructions (innovations) and social constructions (legislations and regulations). My answer – inspired by discussions with Paul Timmers – to this is, that the “right time” for potential regulatory interventions depends on the available technological choices. As soon as the technological construction (innovation) is casted in stone as it were (i.e., no choices are available), it is too late for an agile policy making. This shows that timing is very critical and calls for more research on how to better manage the innovation-regulation system.

Ultimately, however, it is always a trade-off between the possible opportunities and benefits for society and the individual on the one hand and the possible threats on the other. Unfortunately, in Europe these trade-offs are often subject to a kind of spontaneous reflex in the direction of defense against supposed threats. Figuratively speaking, many proposals around digitization are often immediately sacrificed on the altar of data protection without a balanced discussion. The telling opinion of a prominent data protection expert, for example, falls into this category. In essence, he said, in the context with the intended travel facilitation and Covid-19 access rules to events, restaurants, etc., that from a data protection point of view it would be best to stay with the analog vaccination card (on paper) instead of a digital solution.

From a psychological and sociological perspective, it is remarkable that there are apparently people who, for example, have strong doubts about the security of a government digital health portal that is supposed to be run under democratic accountability, and at the same time share many private things on social media platforms completely outside their control with an incalculable number of other people without much concern. That’s why it’s impossible to remind people often enough of the rule: If the product is free, you are the product!.

Starting from my working assumption above, that industry, policymakers, consultants, and regulators are all equally smart on average, the issue of the “right time” for regulatory intervention leads also to the question of the distribution of power between these groups. Obviously, power is not evenly distributed, and the risk of capture is not negligible. This important aspect motivates for further research in this area (see section 7.).

6.3. The disruptive evolution of the ICT ecosystem over the last 20+ years

It’s worth looking back to see what the ICT-ecosystem looked like in 2000:

-

We had narrowband Internet (dial up, DSL, DOCSIS 1.0, GPRS).

-

The ICT-ecosystem was relatively simple, the regulatory mission was clear, and the telecom world was manageable.

-

Regulation 1.0 (1990 – 2000) transformed inefficient monopolies into a competitive landscape, which was rightly hailed as a success.

-

The counterfactual situation would be a continuing inefficient monopoly.

Only twenty years later (2020+), we see a diametrically contrasting-ICT ecosystem:

-

In today’s world, we are faced with a highly complex and highly competitive ecosystem with many ramifications – the counterfactual is unclear.

-

Universal broadband connectivity is one of the focus areas.

-

The balance of market power has completely shifted, but still most (>50%) of the regulatory burden is on the telcos.

-

GAFA’s[11] are only subject to antitrust and since the introduction of EECC subject to very little telecom regulation in some areas.

-

Monetization options for telcos are shrinking; EU Net Neutrality rules are limiting monetization options for telcos. However, supporters of strictly applying BEREC’s Net Neutrality rules argue that while they may be restrictive for telcos, they can have a positive impact on downstream value chain elements. I think that even if this were true, it would be of little consolation to the telecom companies.

-

Telcos have no countervailing buyer power over content providers.

-

Monthly subscription fee is limited upwards by competition.

-

Video streaming traffic is exploding and has a massive carbon footprint. If imposed, digital taxes should be designed to encourage investment in infrastructure (for example a transit fee for telcos) and energy saving measures.

-

Regulatory relief should primarily come through targeted deregulation for the highly regulated sector, and more regulation for the unregulated players. This is in stark contrast to other ideas like new or additional regulatory measures for all players.

-

If regulation seems necessary, then only well justified and very targeted, e.g., to protect essential services, reduce climate-damaging processes or prevent congestion.

6.4. Threats and Opportunities for Traditional Mobile Network Operators (MNOs)

MNOs and their integrated business model are facing major threats but also interesting opportunities, leading to important strategic challenges. The following illustrative and non-exhaustive list shows prospective positive and negative factors for MNOs:

6.4.1. Disruption of the traditional B2C/B2B businesses

-

Traditional B2C communication business (video and voice calls) goes with increasing speed to the digital platforms (Facebook, Google, Skype, Face Time, etc.)

-

Traditional B2B communication business (video and voice calls, collaboration, document sharing) is increasingly going to Microsoft (Teams). Other players like Avaya for example, are moving in the same direction.

-

The traditional vertical structure of integrated mobile carriers stands in the way of industrial implementation, so private networks will boom.

-

The B2B customized network slicing business requires a different set-up for the mobile carrier than the mass production of standardized B2C products.[12]

-

Now, one could say that at least the provision of connectivity remains with the traditional carriers. Are you sure? Facebook, Google, Microsoft could acquire spectrum themselves or rent it from wireless carriers or get access via satellite operators.

6.4.2. Cloudification, Network Slicing and New Operator Paradigms

-

Cloud providers like Azure or AWS can and will provide connectivity with novel connectivity technologies. A perfect example for this option is the very recent Google Cloud deal with SpaceX’s Starlink satellite broadband service, to pair its data centers with satellite-based connectivity. This move is aimed at extending the reach of the edge cloud.

-

“Network Cloudification”: For example, Nokia strikes 5G cloud deals with AWS, Azure and Google. These partnerships will pave the way for new type of 5G services as Nokia integrates its networking technology with the biggest cloud platforms. This is a massive paradigm shift for network operation.

-

Neutral hosts offering connectivity for In-house, shopping malls and even the central London “Square Mile”. Another example, also from London is a neutral 4G/5G network for the London Underground. Universal roaming between service providers active on this neutral host could become a regulatory issue among others.

-

Local operator paradigm: They serve industrial facilities, factories, or ports instead of (or in cooperation with) traditional carriers. New regulatory issues will arise here. “A million private 5G networks by 2030? A million just in Europe, says Vodafone!”.

Example: A new report from Vodafone entitled ‘Powering Up Manufacturing, Levelling Up Britain’, using economic analysis from WPI Economics, suggests that 5G could be a game changer for UK industry, especially for areas digitally ‘left behind’, such as the North West, North East, East and West Midlands, and Wales. According to a recent report from Total Telecom, Vodafone’s research suggests that the efficiency and productivity gains arising from the deployment of private 5G networks could transform the traditional UK manufacturing industry over the next decade, with the improved efficiency and higher productivity achieved through smart manufacturing processes adding up to £6.3 billion to the UK economy by 2030.

6.4.3. Asset Monetization and Reconfiguring Telco Assets

-

Asset Monetization and reconfiguring of telco assets[13] like selling the RAN to Tower Companies or selling edge data centers to cloud providers. Alternatively, MNOs could keep the edge data centers and become cloud providers by themselves. This corresponds to a backward integration of the transport-value-chain that might especially effective e.g., in the IoT, the video or the B2B slicing segment.

-

These options are raising interesting follow up questions:

-

Will a wireless carrier without a RAN turn into a novel kind of MVNO?

-

Or will a wireless carrier with the RAN under his own control develop towards a novel type of cloud-provider?

-

What is left of an MNO if, under the paradigm of asset monetization, the MNO decides to sell not only the RAN but even the entire network or network operations? A novel type of re-seller?

-

Liberty Global has announced a new joint venture (JV) with digital infrastructure fund Digital Colony, aiming to create a European edge data center business with around 120 active data center locations.

-

6.4.4. The MNO – Vendor Relationship Reloaded

-

The MNO-vendor relationship is subject to significant changes – openRAN driven by major telcos may revolutionize the vendor market and at the same time create new challenges (system integration, electric power consumption, potentially new bottlenecks). It might be, that there will be increased pressure on Cisco, for example, to acquire companies like Mavenir or Altiostar.[14] Following Microsoft’s moves (acquisition of Affirmed Networksand Metaswitch Networks in 2020), this would mean a massive shift of relevant industry expertise to the US.

6.4.5. New Opportunities for Telcos

-

On the other hand, 5G offers new opportunities for telcos as outlined above in the area of cloud or virtualization ecosystems. In addition, new opportunities arise in the field of media ecosystems and the relation with broadcasting and content firms. With the rapid growth in video-on-demand services, the long-standing boundaries between telecoms and broadcasting are fading fast. By working together, the two industries can create a compelling proposition for users underpinned by high-capacity, low latency connectivity.

-

5G is a game-changer in mobile broadband services, not only in terms of data speeds and low latencies. With new types of digitally phased array antennas, 5G will be the first architecture to combine terrestrial networks and non-terrestrial network (NTN) platforms – such as HAPs and LEO satellite constellations – into a hybrid network, providing truly ubiquitous mobile broadband and new revenue opportunities across the ecosystem.[15]

6.4.6. 5G Changes User Behavior

-

5G is changing the way people use their phones. That is the gist of Ericsson’s latest ConsumerLab report, which found that one in five 5G users are reducing Wi-Fi use on their phones indoors[16] as they become more aware of the potential benefits of 5G connectivity. Early adopters of the technology are also spending an average of two hours more on cloud gaming and one hour more on augmented reality (AR) apps per week compared to those pitiful, stuck-in-the-mud 4G users. However, 70% of those asked, say they are dissatisfied with the „availability of innovative services and new apps“ in the 5G realm.

All these developments are turning the strategic and regulatory agenda and priorities for MNOs upside down and at the same time create new challenges for the relevant authorities.

The initially successful Regulation 1.0 (1990 – 2003) transformed in nearly all European countries inefficient monopolies into a vibrant competitive landscape, but since then regulation has often taken on an institutional life of its own and has sometimes become petrified. This is the “more-of-the-same” or “proven recipes” phenomenon. Naturally, regulators not only want to keep their jobs but also seek to expand their power. I am aware that, according to the textbook, regulators and other authorities do not define their work for themselves, but that they act on the basis of a legal mandate. However, it would be remote from everyday life to assume that regulators have no influence on legislation. For more details see here.

As a result of this, most of the EU telcos are caught in a trap between declining ARPUs, high CAPEX and only few opportunities to find and leverage new revenue streams. This sobering situation is not only due to sometimes failed regulatory policies (“Let’s stick to proven recipes”) and wrong regulatory incentives but also to insufficient and often entrenched communication between telcos and the political sphere. Now that digitalization has taken hold of every area of the economy, traditional industries are wishing to get in touch with the key player in the process, the telecoms industry. This is particularly true for the energy sector, the automotive industry, healthcare, mechanical engineering, aviation and aerospace, logistics, and the media industry. Yet such ‘verticals’ have the problem of who to call to get in touch with the telecoms industry. The situation is reminiscent of the famous question attributed to former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “When I want to talk to Europe, what number do I call?”. For more details, see also my thought piece “A new Public Policy approach for the European Telecom Industry”.

To conclude, both the telecom and digital sector on the one hand and the relevant authorities on the other hand need change:

-

Telcos need a new policy narrative to prepare the ground for an improved level playing field and to identify new revenue streams. To put it in a nutshell, against the backdrop of the highly complex ICT-Ecosystem 2020, an effective and helpful regulation today would have to say more often „relax, let’s sandbox new ideas (innovations) without limiting ourselves“ instead of „regulate first“. It is also important to remember that the introduction of sector-specific competition oversight, aka regulators, was intended as a temporary transitional regime, without any specific sunset clause attached to it.

-

The relevant authorities (policymakers, telecom regulators, media regulators, competition authorities, digital agencies, etc.) need to get out of their often-entrenched ways of doing things and form new types of cooperation with each other and with market players. Agile policy making, anticipatory regulation and sandboxing could be helpful tools for achieving better regulatory outcomes.

However, this cannot be achieved by flipping a switch, but requires – at least conceptually – a change in the innovation–regulation system. On the industry side a well-thought-out strategic approach is needed, starting with sound academic work and convincing policy papers to open a new chapter in government relations. This must be accompanied by a comprehensive communication strategy to convince politicians, industry representatives/associations and regulators. On the side of the authorities, it all starts with the political ambition to change the situation for the better. Against the background of the massive changes explained in this article, there is room for improvement of the institutional set-up in many jurisdictions. A benchmark was set in the UK, when the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Office of Communications (Ofcom) formed the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) in July 2020. Building on the strong working relationships between these organizations, the forum was established to ensure a greater level of cooperation, given the unique challenges posed by regulation of online platforms.

Telcos need a New Deal with politics! In any case, there is a plethora of strategic issues ahead of us!

7. Outlook and potential future research areas

While working on this policy paper, I noticed a few points that seem worth exploring in more detail. Here are a few examples:

Regulatory innovations: It would be worth exploring, how best practice examples of regulatory innovations such as anticipatory regulation or sandboxing and agile policy making can be successfully transferred into the telecom ecosystem. This regards all competent authorities in this field (regulators, general competition authorities, digital agencies, R&D establishments, etc.) and relevant ministries. I am aware that introducing regulatory innovations also requires challenging and time-consuming debates with regulatory orthodoxy.

Innovation – Regulation System: The „right time“ for eventual regulation depends inter alia on the question when an innovation becomes socially, politically, technically, or economically relevant. The issue of relevance could be defined, for example, by a set of criteria, like the number of available technology options. The relevant research question would be, how can we set up a system which is able to better synchronize technological constructions (innovations) and social constructions (legislations and regulations). An additional aspect could be to unpack how to regulate an industry that is, at least partially, governed by exponential growth in performance. It could also be interesting to think about regulation from the complex systems perspective and to better “connect the dots”.

The introduction of a regulated transit fee would be a possible solution to a persistent problem, the massively growing imbalance between telcos and digital platforms. Telcos need to make significant infrastructure investments to handle the rapidly growing video traffic generated by global streaming providers. The major streaming providers generate approx. 60-80% of global download traffic. This trend is increasing, with video as a killer app, and the pandemic worked as an accelerator for this development. The relevant research question would be how to design a kind of regulated transit fee for the telcos and what would be the market failure to justify a potential regulation. BEREC already addressed this issue in 2016 in a workshop in co-operation with the OECD, but that was 5 years ago, and things have changed significantly since then, in particular against the evidence collected during the pandemic.

Socioeconomic impacts of broadband; potential outcome variables e.g. (regional) GDP, (local) labor market variables, education; broadband variables measured by e.g., connected lines, infrastructure available or speed levels; testing overall effect as well as diminishing returns of speed /quality levels and / or regional spill-over effects.

The impact of ICT on GHG emissions and on electricity consumption; discussing heterogenous direct and indirect effects of ICT on GHG emissions and electricity consumption and testing overall effect as well as interaction effects using various ICT measures.

As discussed in Section 6.3, the BEREC net neutrality rules (or the way they are applied) restrict monetization options for telecommunications companies. However, advocates of strict net neutrality rules argue that while they are restrictive (and thus harmful) to telecommunications companies, they can have positive effects on downstream elements of the value chain. It would be worthwhile to critically assess this view ex-post. The US may provide an interesting example, as they relaxed the net neutrality rules, they had in 2015-2018 under the Trump Administration and we are now seeing discussion of reviving them under the new Administration.

Starting from my working assumption in section 6.1, that industry, policymakers, consultants, and regulators are all equally smart on average, the issue of the “right time” for regulatory intervention leads also to the question of the distribution of power between these groups. Obviously, power is not evenly distributed, and the risk of capture is not negligible. This important aspect motivates for further research in this area.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

Work in progress: As mentioned earlier, this paper reflects my current thinking on the relationship between regulation and innovation, and what policies are best suited to foster innovation from a regulatory perspective. It is a work in progress, and I may revise and add to my views after further discussion results, review, and analysis of new data and materials. Readers are invited to contribute to this discussion.

Telecommunications companies, an endangered species: Against the backdrop of the factors described here, it may be that the telecommunications industry will lose, or has already lost, its original key and universal role in the electronic communications market. In this case, it seems more likely, that the Microsoft’s and Google’s of this world would be the ones, the above mentioned ‘verticals’ would “call”. Whether one likes this result or not, the fact remains in my assessment that most telecommunications companies in Europe have so far not – or only incompletely – succeeded in establishing additional services beyond the provision of connectivity successfully on the market on a sustained basis under the current conditions (especially under the pressure of OTTs and regulation). In addition, many telecom companies are not managed according to the principles of long-term infrastructure investment but are managed under the pressure of short-term financial results.

Focus on connectivity: Perhaps under these conditions, it would be worth considering as a telecommunications company to focus on creating ubiquitous connectivity with customized service levels? Surely that’s not a bad thing? Or is it? There is not much time for that either, because the OTTs themselves are striving to provide connectivity (see section 6.4.1.). The discussions about the introduction of openRAN on a large scale in particular have made it clear to all stakeholders that it is necessary to build up more technical capacities in the telecom companies in order, for example, to carry out the system integration of the components themselves.

This sobering scenario calls for setting-up a unified industry association for the telecom industry capable of speaking on behalf of all those who provide connectivity. I suggest that telecommunications companies consider organizing themselves better collectively to stop this development or change its course or to develop sustainable alternatives. In these exciting years from 1990 to today, we have seen the metamorphosis of telcos from technology companies to marketing companies and infrastructure providers. Perhaps it is time for telcos to become technology companies again to a greater extent, not only providing high quality and secure infrastructure and delivering it to consumers and businesses, but also being more active on the technology front again. The thinking behind the open RAN MoU of four major telecom companies (plus one company joining later) could be interpreted as an initiative in this direction. The overarching strategic question is whether it makes sense for telcos to enter a battle with the platforms that has already been lost once. See also my thought piece “A new Public Policy approach for the European Telecom Industry”.

How to navigate the changing landscape: According to the McKinsey Study “Automotive software and electronics 2030”, important learnings can be derived from the automotive sector: “If solutions for challenges are not yet set in stone, be ready to experiment as there is no silver bullet yet. Players that want to be successful in the emerging technologies, […] will need to embrace a test-and-learn culture and be ready to experiment and quickly iterate learnings”.

The new Regulation 4.0 (in particular the DMA proposals) is likely to come into force in 18-24 months and will need to be reconciled with existing competition law in a way that works pragmatically. However, this will only function satisfactorily for all stakeholders – including gatekeepers – if the two regimes operate in a consistent, complementary, and harmonious manner. We all know that the European lawmaking process is long and arduous and that we can expect a lot of lobbying and resistance along the way. For certain, all stakeholders will have to compromise before the DMA can be enacted.

I suggest creating a BEREC working group to look at regulatory innovation, applicable best practices from other sectors, and implementing sandboxes in the regulatory practice. Members of this working group could support NRAs to experiment with these innovations.

After all, the more complex and sophisticated ICT ecosystem 2020+ also requires a revised working relationship between the relevant authorities. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Office of Communications (Ofcom) formed the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) in July 2020. Building on the strong working relationships between these organizations, the forum was established to ensure a greater level of cooperation, given the unique challenges posed by regulation of online platforms. More courage to experiment would be a fitting action paradigm for both industry and regulators.

9. Closing Remarks and Acknowledgements

A final important comment on my own behalf at the end of these remarks, so that my position is not misinterpreted: When I talk about the need for deregulation or smarter regulation in some areas to give innovation and digitization more freedom, this presupposes that the job of Regulation 1.0 has also been properly accomplished in the respective jurisdiction. If this has not been achieved, there is no need to talk about deregulation. Of course, there are also abuses or attempts to force rivals out of the market in developed competition systems, but to fight this does not require ex ante sector-specific oversight. For such cases, there are the competition authorities.

Acknowledgments: I am very grateful for critical remarks and many insightful and inspiring discussions with representatives from the regulatory community, friends, and business partners, and with my Squire Patton Boggs colleagues. Finally, my colleagues from the “Brown-Bag-Lunch” group (in alphabetic order) Sanja Boltek, Derk Oldenburg, Paul Timmers, Paulo Valente and Wolfgang Weber played a key role with many valuable contributions.

10. Annex – The EU Digital Agenda

10.1. The Big Picture

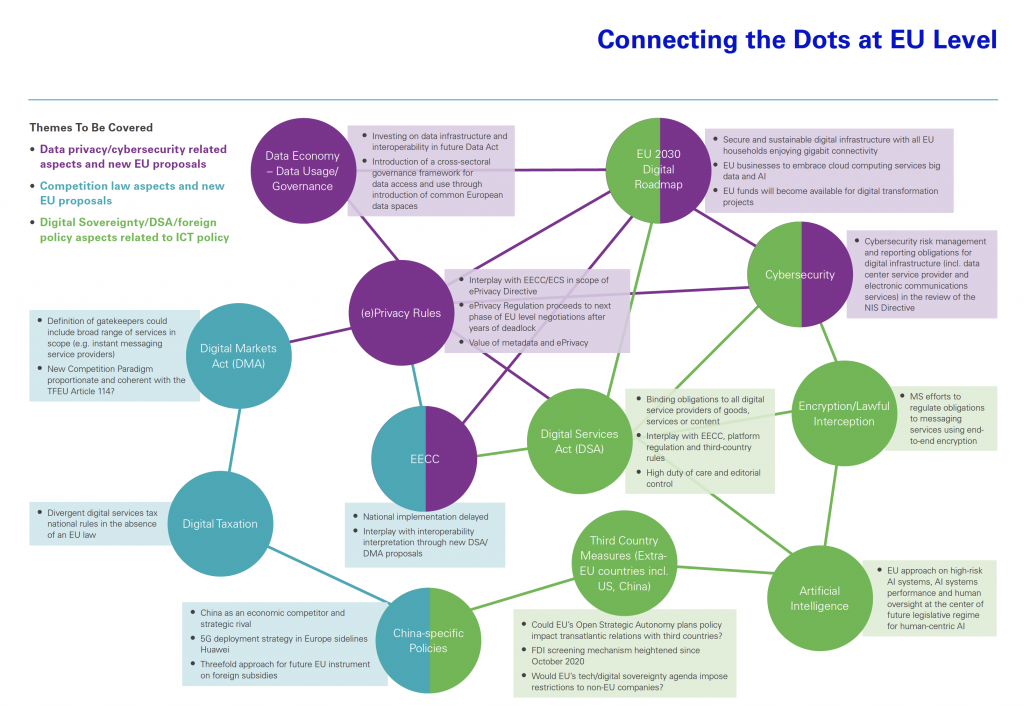

The European Commission and the EU co-legislators (Parliament and Council) are currently pursuing several new digital policy goals. To understand the legislative process, it is important to know the overarching policy concerns and priorities, to follow their evolution, and to understand how the different initiatives are interconnected. The EC proposals target three broad themes: (1) „digital sovereignty,“ (2) data protection and cybersecurity, and (3) consumer protection and competition in the digital marketplace.

Based on these issues, several policy priorities can be identified:

-